ScienceVet’s Sex Spectrum

This rebuttal appears in an expanded form in Binary, a book published by the Paradox Institute.

ScienceVet’s thread on the sex spectrum is one of the most shared pieces on the subject. Let’s break it down and analyze the details of his argument with peer-reviewed science.

Citations numbered below (with direct links).

Read ScienceVet’s original thread here.

Part One: Defining Sex

ScienceVet’s premise is that sex is not binary (either/or), but rather a spectrum comprised of variation in anatomy and physiology. He’s correct that there is indeed a spectrum of anatomy and physiology, but does this make a spectrum of sex?

He begins by defining sex as “body parts, hormones, and genetics (and more).” He says that because of this variation in body parts, hormones, and genetics, biological sex is a spectrum. However, this variation in anatomy and physiology represents sex-related traits, not sex.

Let’s define sex: Sex is the type of gamete one’s reproductive anatomy is organized to support. Males are the sex which develop reproductive anatomy organized to support sperm, and females are the sex which develop reproductive anatomy organized to support ova.[1]

The fusion of two gametes of differing size is known as anisogamy, and it’s the fundamental definition of sex in anisogamic species. Any description which leaves out what sex is in the first place (the two evolved reproductive functions) is not describing sex.[2][3]

Thus, what continues after ScienceVet’s first tweet is a description of the complex variation in anatomy and physiology within males and within females. It is this complexity that allows him to claim we cannot reliably define male and female while ignoring the definition of sex.

Part Two: Sex Development

ScienceVet begins this section by using congenital medical conditions of the reproductive tract (DSDs) to argue that the dichotomy of XX = female and XY = male we learned in 4th grade is false. Let’s explore what he presents as evidence.

Tweet 3, he writes, “There are XY people, who have ovaries! And give birth! And XX people who have male bodies and functional sperm.” It may sound confusing at first, but a closer look at these two cases shows the simple truth of the sex binary.

The XY woman giving birth had a mosaic karyotype, where some of her cells were 46,XY, and others were 45,X and 46,XX. Because she developed a reproductive system organized to support large gametes, she’s female. That’s why she had ovaries and was able to give birth.[4]

The XX males do exist, with testes and a penis, but they do not have functional sperm (only immature sperm cells due to lacking the AZF region from the Y chromosome). XX males result from a translocation of the SRY gene onto an X chromosome during germ cell division. Because the SRY gene is present, it initiates gonadal differentiation into testes, and the fetus develops anatomy to support small gametes.[5]

Thus, based on the fundamental definition of sex (the two evolved reproductive anatomies to support two gametes) we can see that the two cases ScienceVet brings up are not variations outside the binary, but rather, variations within.

ScienceVet continues by listing more variations in anatomy and physiology. He writes, “[There’s] (XXY, XYY, Y, X, XX with translocation, XY with deletion) to hormonal (Androgen Insensitivity, Estradiol failure)” This is true, but all of these cases are still male or female. Why?

XXY individuals develop as males thanks to the activation of the SRY gene. Y fetuses do not survive (because 1 X chromosome is required for development). XX with translocation is the XX male case described above, and XY with deletion results in female development.[6][7]

Thus, rather than proving sex itself is on a spectrum, these cases show us the amazing stability of the two evolved reproductive anatomies, and thus, the stability of the sex binary. Even with chromosomal or hormonal anomalies, the fetus still develops as a male or female.[8]

Part Three: Bimodality

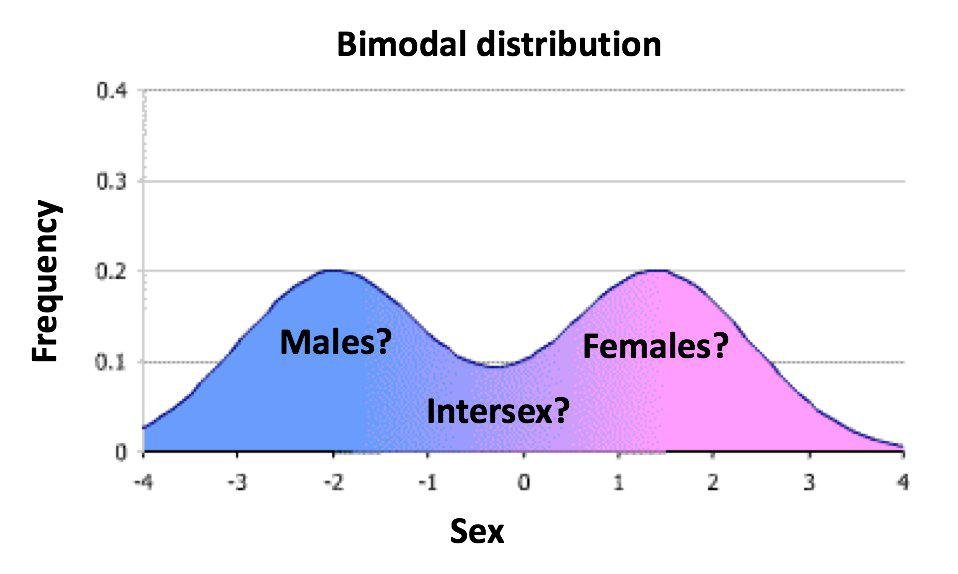

After presenting these variations in body parts, hormones, and genetics, ScienceVet says that we aggregate all these traits together and put them on a bimodal distribution, with “two big peaks we call ‘male’ and ‘female.’”

This is not how sex differences work. The two big peaks are not male and female. Rather, the two big peaks represent the AVERAGE of a given trait for males and AVERAGE of a given trait for females. The correct bimodal graph shows a separate bell curve for males, and a separate curve for females.

For example, take sex differences in height. There is a distribution of height for males and a distribution of height for females. Overlap does not mean we cannot define male and female, but rather, shows where males and females share a common set of height values.[9]

ScienceVet’s point is that we categorize male and female based on averages, and because there are people who fall outside the averages, the categories of male and female do not represent the full variation.

But ScienceVet can only say this if male and female are defined as averages of body parts, hormones, and genetics. As we have discussed, male and female are not averages of anatomy and physiology, but rather, describe the two evolved reproductive anatomies.[10]

A bimodal distribution for males and females means that there is variation within males and variation within females. A short male does not suddenly become a female, and a female with a lot of testosterone does not suddenly become a male. Thus, variation does not equal sex.[11]

Ironically, ScienceVet’s premise that male and female are defined as two peaks (averages) implies that male and female are defined through stereotypes, and that anyone falling outside of these averages (or stereotypes) is not a complete ‘male’ or ‘female.’

This is the logical conclusion of the argument that sex itself can be placed on a continuous quantitative axis as ScienceVet describes. Some males would be more male than others, and some females would be more female than others. Sound regressive? That’s because it is.

The only reason we have a bimodal distribution for males and females in the first place is because sex is binary.

Part Four: Individual Variation

With the assumption that male and female are just averages of anatomy and physiology, not distinct categories, ScienceVet then claims that there is nothing stopping us from binning every individual into their own bin of sex. He claims this would mean we’d have 7.4 billion sexes.

It’s true that there is variation in brain areas, hormone levels, signaling differences, and genetic variances (as ScienceVet writes), but such variation does not mean male and female cannot be defined, and it does not mean someone who has atypical traits is not male or female.

What does such variation mean? It means that within males and within females, there is a variety of anatomy and physiology. One’s sex is still defined through the type of gamete one’s reproductive system is organized to support. And this system is 99.98% consistent.[12]

Part Five: Conclusion

ScienceVet is right that we need highly individualized, evidence-based medicine that rejects narrow assumptions of how male and female bodies should respond to treatments. In other words, we should continue to explore the variation within and between males and females.[13][14]

But he’s wrong in claiming that variation of anatomy and physiology within and between males and females means that sex is on a spectrum. There are only two evolved reproductive anatomies to support two gametes, and thus, only two sexes.

Rather than expanding the definition of male and female, as ScienceVet claims we must do to apply accurate medical treatments, we need to better understand the processes which form the variation WITHIN males and variation WITHIN females.[15]

As developmental biologist Dr. Emma Hilton (@FondOfBeetles) writes, “It’s not that ‘male’ or ‘female’ boxes have to get bigger, it’s that our understanding of the mechanisms that make males and females has to absorb new data.”

Thus, to conclude, ScienceVet’s thread uses a common pattern seen among all sex spectrum arguments: obfuscating the true definition of sex by using variation of anatomy and physiology to claim that male and female cannot be reliably defined.

The Pattern

1) Ignore the fundamental definition of sex.

2) Claim that sex is defined through variation in body parts, hormones, and genetics.

3) Present variation of sex-related traits and complex medical conditions as evidence that sex is a spectrum.

4) Use this complexity to argue that male and female are not reliable categories.

ScienceVet makes interesting points, but because he never defines sex and instead utilizes variation in anatomy and physiology, and incorrectly argues that male and female are defined through “average” traits, his claim that sex is a spectrum is false.

Sex is defined through two evolved reproductive anatomies to support two gametes. Within this system, there is a variety of anatomy and physiology (such as hormone levels), with average traits for males and average traits for females.

Thus, it is the variety of traits within males and within females that is bimodal, not male and female itself. The truth is that sex is binary, and we do not have to deny this fact to accept and celebrate the wide diversity of body types, psychology, and expression found within it.

Editor’s correction: This article originally used ScienceVet’s claim that XX males have “functional” sperm when discussing the definition of sex. In reality, no XX male has been known to have functional sperm, only immature sperm cells that have not progressed through the full differentiation process. Thus, XX males are all infertile. The article has since been corrected.

[2] Czaran, T., Hoekstra. R. (2004). Evolution of sexual asymmetry. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 4(34).

[3] Marinov, GK. (2020). In humans, sex is binary and immutable. Academic Quest.

[5] Kimball, J. (2020). Sex chromosomes. LibreText.org.

[9] Schmitt, P. (2017). Sex and Gender are Dials (Not Switches), Psychology Today.

[10] Hilton, E., Wright, C. (2020). The Dangerous Denial of Sex. Wall Street Journal.

[11] Schmitt, P. (2017).

[12] Sax, L. (2002). How common is intersex? A response to Anne Fausto-Sterling. Journal of Sex Research.

Additional Reading:

[16] Graham, C. (2019). Is sex a spectrum? Sex determination and differentiation. MRKHVoice.

[17] Lewis, A. (2019). Is sex a spectrum? Medium.

[18] Heying, H. (2019) Boundaries in biology are fuzzy, but gametes aren’t. Twitter.

[21] Bachtrog, D., et al. (2014). Sex determination: Why so many ways of doing it? PLOS Biology, 12(7).

Since the first uterine transplant in the US, doctors have been theorizing if a uterus transplant could be possible for a transwoman. Case studies say otherwise.